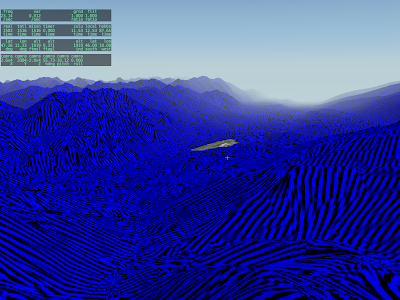

Some of the coolest in-development screen-shots are the bugs. A few weeks ago while working on cloud shaders I managed to create a hybrid of an acid trip and a light-speed trip on Star Wars. Sadly the code has since been modified a thousand times and the effect is gone.

So I’m going to start posting bizarre images as they crop up. Usually they don’t reveal too much about unreleased features.

This came out of some experiments with hills, mountains and UV mapping.

(Clearly what this code needs is a leopard-print texture.)

Normal maps in X-Plane 940 have a funny property: if you flip the normal map horizontally or vertically, the bumps change direction. Things that “stuck out” now “stick in” and vice versa. (If you flip the normal map horizontally and vertically, the two cancel out and the normal map is not reversed.)

You can understand this by thinking of your normal map as a physical piece of metal with bumps punched in it. Flipping it horizontally really means rotating it horizontally to see the other side – now you see the back side of the bumps. Same with the vertical flip. Flip both and you have flipped it twice and it’s front-side forward again.

In a move that is either just in the nick of time or dangerously reckless, I have tweaked the normal map shader for 950 RC1 (coming out “real soon”) to detect and “fix” a flipped normal. In 950 rc1 the bumps in your normal map will always point in the same direction as the normal of your mesh, even if your UV map is flipped horizontally or vertically.

What does this mean to you, the modeler? It means that you can now mirror your normal map from the left to the right side of the airplane and the normal map will still have the bumps “sticking out” like you want.

I crammed this into 950 RC 1 because it looks like it’s a useful change that will restore flexibility to authors making highly detailed airplanes. Mirroring a symmetric airplane (which results in a horizontally mirrored normal map) is a pretty common thing to do, and if the text is applied as decals, this can be a big win in texture space savings.

I figured best to get the tweak in here now so people could take advantage of it. Plus, what’s an RC1 without an RC2?

It goes without saying that this post was, um, inaccurate.

This, however, is real.

I wasn’t planning on discussing this until April 3rd, but some sites have already picked it up, so I might as well explain the why behind it. Simply put: X-Plane 10 will be for the iPad only. I figure that by letting you know now, you can make an informed decision about whether you want to buy an iPad. (Hint: you do!)

This wasn’t an easy decision to make, but here were some of the deciding factors:

-

I spend a lot of my time debugging video drivers, and it makes me very grumpy. You guys seem to think that you can plug anything with copper and wires into your PCIe socket and call it a “video card”. By restricting version 10 to iPad only, we cut down development time by targeting only one GPU.

-

We love everything Steve Jobs does and kiss the ground he walks on. Steve says the pad is magical.

-

The biggest single feature request we get for X-Plane is “can I use X-Plane while operating a motor vehicle.” X-Plane 9’s requirement of 1 GB of RAM, a modern CPU, etc. means that most X-Plane 9 machines are not particularly portable. By making X-Plane 10 iPad only, we can provide X-Plane in a portable format that’s more compatible with flying a flight simulator while driving.

One fringe benefit to cockpit builders: because the iPad is so light and thin, creation of a realistic home cockpit with X-Plane 10 will be easier than ever. Simply take some super-glue, wipe it on the back of your iPad, and simply “stick” the iPad to whatever part of the cockpit you want. It’s so easy a four-year-old could do it!

OS X 10.6.3 is out. Besides adding a bunch of OpenGL extensions*, it looks like vertex performance is improved on nVidia hardware. My quick tests compare 10.5.8 to 10.6.3 (since I no longer have a 10.6.2 partition) and show a 15-30% improvement. If you have 10.5 and an 8800 you may want to consider updating your OS.

I also discovered that –fps_test=3 produces unreliable results because…wait for it…the deer and birds are randomized. If they show up during the fps test, you get hit with a performance penalty. I am working to correct this and may have to recut the time demo to work around this behavior.

If you are trying to time the sim via –fps_test=3, I suggest running the test multiple times – you should see “fast” runs and “slow” runs depending on our feathered and four-legged friends.

Phoronix reported a performance penalty with the new update; I do not know the cause of this or whether the fps_test=3 bug could be causing it. But their test setup is very different than mine – a GeForce 9400 on a big screen, which really tests shading power. My setup (an 8800 on a small screen) tests vertex throughput, since that has been my main concern with NV drivers.

My suggestion is to use –fps_test=2 if you want to differential 10.6.2 vs. 10.6.3. I’ll try to run some additional bench-marks soon!

EDIT: Follow-up. I set the X-Plane 945 time demo to 2560 x 1024, 16x FSAA, and all shaders on (e.g. let’s use some fill rate). I put the Cirrus jet on runway 8 at LOWI, then set paused forward full screen no HUD. In this configuration, I see these results:

Objects 10.5.8 10.6.3

none 85 fps 100 fps

a lot 46 fps 61 fps

tons 37 fps 42 fps

Note that in the “no objects” case the sim is fill-rate bound – in the other two it is vertex bound. So it looks to me like 10.6.3 is faster than 10.5.8 for both CPU use/object throughput and perhaps fill rate (or at least, fill-rate heavy cases don’t appear to be worse).

* These extensions represent Apple and the graphics card company creating software interface to fully unlock the graphics card’s abilities.

If you look at funky pictures of X-Plane on line, a fair number of them will show incorrect water reflections. I am working on some bug fixes for the reflection code for 950. Bug fixes might not even be the right term. To understand the incorrect reflections, you have to understand what the water code can and cannot do.

The water reflection code renders a reflection based on a flat plane. This limitation comes from the mathematics of the algorithm – a compromise to have water reflections that run at “real-time” speeds. (Real-time is graphics nerd speak for 20-30 fps and not 1-2 fps.)

As it turns out, the Earth is not flat. So we can pick up a number of reflection “bugs”, due to the limits of the approximation we are using:

- Over very large distances, the flat plane is a bad approximation of a water surface. The flat plane simply can’t be “right” everywhere for any large scene. This isn’t a bug, it’s a ceiling on our maximum quality – a design constraint.

- If we have two water surfaces at different elevations (e.g. a river with a dam) we can’t have our reflection plane match both. So some scenes may have wrong reflections with multi-level water. This too is a design constraint.

- If our reflection plane is at the wrong height or the wrong slope, it is going to produce really weird results. The reflection plane being in the wrong place despite a small scene with one level of water – that’d be a bug.

- There is an art to positioning the plane – if we have a large scene (so the round earth means there is no one perfect plane) some locations of the plane will look better than others.

Now one fall-out of all of this is that things are going to look better if water is really flat, which is not always the case (both for some parts of the global scenery with production errors and some third party scenery). Where the water is sloped or contains bumps, we hit the multi-level case where we should not and we face reflection plane placement problems.

Finally, if the scenery mesh contains slanted water, we’re really going to be hosed – almost by definition if X-Plane uses a sane water reflection plane, it won’t be sloped, and thus this sloped water is going to be unaligned with the reflection plane and produce something that looks really funky.

So my work on 950 is aimed at having X-Plane be less easily fooled by complex and incorrect scenes less often. (Note that X-Plane can’t tell the difference between Norway, where we really have water at multiple elevations, and bad input data to MeshTool.)

Even with these fixes, sloped water is still going to look pretty strange (because it is strange). And even with these fixes, multi-level water will still have its reflections approximated at best. But hopefully the visuals from the sim will be less jittery while flying over tricky DSFs.

I’m hoping we’ll have a beta 2 in the next week or two.

Now that Wade has XSquawkBox 1.0.3 out, I’ve been thinking about CSLs – that is, the collections of simplified airplanes that XSquawkBox uses to draw the other users. The CSL system was invented back in the days of X-Plane 6, and it’s getting a bit long in the tooth. You can’t use OBJ8 files, and it doesn’t understand a lot of the modern rendering tricks that authors use with the standard tool chain.

Plane-Maker has advanced quite a bit since then too – to make the original CSL, I had to create a special one-off hacked build of Plane-Maker to export aircraft as OBJs. This capability is now built into Plane-Maker, works a lot better, and even supports animation.

X-Plane now exports a native OBJ drawing interface to plugins. Besides giving plugins access to the fully optimized native OBJ draw code, this also means that plugins can draw objects with per-pixel lighting.

One more piece of the puzzle: in France Austin announced that we were working on a new ATC engine. One goal of this new engine is to provide ATC to the AI planes, as well as your plane, so that the other aircraft interact seamlessly in one simulated environment. (In X-Plane 9, ATC only directs you, and the AI are rogue planes that try not to buzz you when you’re on the runway.)

This makes me wonder: should there be a next-gen CSL format that is shared between X-Plane and third parties, based on X-Plane doing the rendering work?

Wade just cut the final build for XSquawkBox 1.0.3, and of all of the betas I have been involved in, this was the best one ever. I say this because Wade ran the entire beta and fixed pretty much all of the bugs without me! That is to say, Wade made 1.0.3 happen. So huge thanks to Wade for making a new and much needed XSquawkBox version possible.

Here are some of the features:

- Automatic download and update of the server list.

- Dual VoIP radios.

- Proxy client support for users with multiple copies of X-Plane for multiple views.

- A ton of work on the UI – a lot of little things add up to make a much more mature, usable client.

Now if only I had time to fly on VATSIM…

This isn’t supposed to be a coding blog, but users do ask about DirectX vs. OpenGL, or sometimes start fights in the forums about which is better (and yes, my dad can beat up your dad!). In past posts I have tried to explain the relationship between OpenGL and DirectX and the effect of OpenGL versions on X-Plane.

At the Game Developers Conference 2010 OpenGL 4.0 was announced, and it looks to me like the released the OpenGL 3.3 specs at almost exactly the same time. So…is there anything interesting here?

A Quick Response

In understanding OpenGL 4.0, let’s keep in mind how OpenGL works: OpenGL gains new capabilities by extensions. This is like a new item appearing on a menu at your favorite restaurant. Today we have two new specials: pickles in cream sauce, and fried potatoes. Fortunately, you don’t have to order everything on the menu.

So what is OpenGL 4.0? It’s a collection of extensions: if an implementation has all of them it can call itself 4.0. An application might not care. If we only want 2 of the 4 extensions, we’re just going to look for those 2 extensions, not sweat what “version number” we have.

Now go back to OpenGL 3.0, and DirectX 10. When DX10 and the GeForce 8800 came out, nVidia published a series of OpenGL extensions that allowed OpenGL applications to use “cool DirectX 10 tricks”. The problem was: the extensions were all NVidia specific tricks. After a fairly long time, OpenGL’s architectural review board (ARB) picked up the specs, and eventually most of them made it into OpenGL 3.0 and 3.1. The process was very slow and very drawn out, with some of these “cool DirectX 10 tricks” only making it into “official” OpenGL now.

If there were OpenGL extensions for DirectX 10, who cares that the ARB was so slow to adopt these standards proposed by NVidia? Well, I do. If NVidia proposes an extension and then ATI proposes a different extension and the ARB doesn’t come up with a unified official extension, then application like X-Plane have to have different code for different video cards. Our work-load doubles, and we can only put in half as many new cool features. Applications like X-Plane depend on unity among the vendors, via the ARB making “official” extensions.

So the most interesting thing about OpenGL 4.0 is how quickly they* made official ARB extensions for OpenGL that match DirectX 11’s capabilities. (NVidia hasn’t even managed to ship a DirectX 11 card yet, ATI’s HD5000 series has only been out for a few months, and OpenGL already has a spec.) OpenGL 4.0 exposes pretty much everything that is interesting in DirectX 11. By having official ARB extensions, developers like Laminar Research now know how we will take advantage of these new cards as we plan new features.

Things I Like

So are any of the new OpenGL 3.3 and 4.0 capabilities interesting? Well, there are three I like:

-

Dual-source blending. It is way beyond this blog to explain what this is or why anyone would care, and it won’t show up as a new OBJ ATTRibute or anything. But this extension does make it possible to optimize some bottlenecks in the internal rendering engine.

-

Instancing. Instancing is the ability to draw a mesh more than one time (with slight variants in each copy) with only one instruction to the graphics card. Since many games (like X-Plane) are limited in their ability to use the CPU to talk to the graphics card (we are “CPU bound” when rendering) the ability to ask for more work with fewer requests is a huge win.

There are a number of different ways to program “instancing” with OpenGL, but this particular extension is the one we prefer. It is not available on NVidia cards right now. So it’s nice to see it make it into the core spec – this is a signal that this particular draw path is considered important and will get attention.

-

The biggest feature in OpenGL 4.0 (and DirectX 11) is tessellation. Tessellation is the ability for the graphics card to turn a crude mesh with a few triangles into a detailed mesh with lots of triangles. You can see ATI demoing this capability here.

There are a lot of other extensions that make up OpenGL 3.3 and 4.0 but those are the big three for us.

* who is “they ” for OpenGL? Well, it’s the architectural review board (ARB) and the Khronos group, but in practice these groups are made up of employees from NVidia, ATI, Apple, Intel, and other companies, so it’s really a collective of people involved in OpenGL use. There’s a lot of input from hardware vendors, but if you read the OpenGL extensions, you’ll sometimes see game development studios get involved; Transgaming and Blizzard show up every now and then.

Tom has a new video on youtube of his just finished Falco. The video shows what screen-shots cannot: that the mouse interactions on the plane are really well crafted.

If you’re just discovering X-Plane (or just discovering that X-Plane’s 3-d cockpits can be very interactive), here’s X-Plane’s “raw” capabilities for manipulation:

- The simplest manipulations are based on mapping the mouse from the 3-d cockpit back to the 2-d panel. This can only be done when the 3-d cockpit is textured using a piece of 2-d panel. This is the oldest way to make a clickable cockpit in X-Plane, dating back to the original X-Plane 3-d cockpits. The advantage of this method is that it’s very easy to set up; the disadvantage is that the mouse click gestures tend to be “flat” in their operation.

- As Tom’s plane demonstrates, you can manipulate just about any dataref or command via a drag along a specific axis. Axes are subject to animation, so there’s a lot of potential for “grabbing” things with this interface.

- X-Plane also supports direct “click” manipulation – this can be handy for buttons where you don’t want to require the user to move the mouse around. There are several types of click manipulation.

Click and drag manipulations can be tied into the plugin system – your plugin sees a manipulation as a change to a plugin-created dataref. This makes it possible to create almost any imaginable mouse effect. If you don’t want to write a plugin, you can still write up the manipulators to any of X-Plane’s datarefs (there are thousands) or commands (we’re getting up toward the 1000 mark on these too).

To create manipulators on your cockpit, you can use the latest plugin for AC3D. A manipulator is a property on a mesh within your object – each mesh can have its own manipulation with its own properties.

X-Plane does not have an IK solver. Rather, movement of “stuff” in your cockpit is indirect.

- Your manipulator changes a dataref as the user drags along an axis.

- The dataref change shows as an animation on your mesh.

Fortunately, ac3d has a “Guess” button for the axis manipulators. If you set a mesh to be manipulated by dragging along an axis, the guess button will examine your animations and suggest an axis that will create the most “natural” looking animation for the manipulation. For example, if you have a throttle handle that rotates, the guess button will provide a drag axis perpendicular to the throttle (to push the levers); if you have a throttle lever that pushes, the guess button will make a drag axis that runs along the lever.