OS X 10.6.3 is out. Besides adding a bunch of OpenGL extensions*, it looks like vertex performance is improved on nVidia hardware. My quick tests compare 10.5.8 to 10.6.3 (since I no longer have a 10.6.2 partition) and show a 15-30% improvement. If you have 10.5 and an 8800 you may want to consider updating your OS.

I also discovered that –fps_test=3 produces unreliable results because…wait for it…the deer and birds are randomized. If they show up during the fps test, you get hit with a performance penalty. I am working to correct this and may have to recut the time demo to work around this behavior.

If you are trying to time the sim via –fps_test=3, I suggest running the test multiple times – you should see “fast” runs and “slow” runs depending on our feathered and four-legged friends.

Phoronix reported a performance penalty with the new update; I do not know the cause of this or whether the fps_test=3 bug could be causing it. But their test setup is very different than mine – a GeForce 9400 on a big screen, which really tests shading power. My setup (an 8800 on a small screen) tests vertex throughput, since that has been my main concern with NV drivers.

My suggestion is to use –fps_test=2 if you want to differential 10.6.2 vs. 10.6.3. I’ll try to run some additional bench-marks soon!

EDIT: Follow-up. I set the X-Plane 945 time demo to 2560 x 1024, 16x FSAA, and all shaders on (e.g. let’s use some fill rate). I put the Cirrus jet on runway 8 at LOWI, then set paused forward full screen no HUD. In this configuration, I see these results:

Objects 10.5.8 10.6.3

none 85 fps 100 fps

a lot 46 fps 61 fps

tons 37 fps 42 fps

Note that in the “no objects” case the sim is fill-rate bound – in the other two it is vertex bound. So it looks to me like 10.6.3 is faster than 10.5.8 for both CPU use/object throughput and perhaps fill rate (or at least, fill-rate heavy cases don’t appear to be worse).

* These extensions represent Apple and the graphics card company creating software interface to fully unlock the graphics card’s abilities.

This isn’t supposed to be a coding blog, but users do ask about DirectX vs. OpenGL, or sometimes start fights in the forums about which is better (and yes, my dad can beat up your dad!). In past posts I have tried to explain the relationship between OpenGL and DirectX and the effect of OpenGL versions on X-Plane.

At the Game Developers Conference 2010 OpenGL 4.0 was announced, and it looks to me like the released the OpenGL 3.3 specs at almost exactly the same time. So…is there anything interesting here?

A Quick Response

In understanding OpenGL 4.0, let’s keep in mind how OpenGL works: OpenGL gains new capabilities by extensions. This is like a new item appearing on a menu at your favorite restaurant. Today we have two new specials: pickles in cream sauce, and fried potatoes. Fortunately, you don’t have to order everything on the menu.

So what is OpenGL 4.0? It’s a collection of extensions: if an implementation has all of them it can call itself 4.0. An application might not care. If we only want 2 of the 4 extensions, we’re just going to look for those 2 extensions, not sweat what “version number” we have.

Now go back to OpenGL 3.0, and DirectX 10. When DX10 and the GeForce 8800 came out, nVidia published a series of OpenGL extensions that allowed OpenGL applications to use “cool DirectX 10 tricks”. The problem was: the extensions were all NVidia specific tricks. After a fairly long time, OpenGL’s architectural review board (ARB) picked up the specs, and eventually most of them made it into OpenGL 3.0 and 3.1. The process was very slow and very drawn out, with some of these “cool DirectX 10 tricks” only making it into “official” OpenGL now.

If there were OpenGL extensions for DirectX 10, who cares that the ARB was so slow to adopt these standards proposed by NVidia? Well, I do. If NVidia proposes an extension and then ATI proposes a different extension and the ARB doesn’t come up with a unified official extension, then application like X-Plane have to have different code for different video cards. Our work-load doubles, and we can only put in half as many new cool features. Applications like X-Plane depend on unity among the vendors, via the ARB making “official” extensions.

So the most interesting thing about OpenGL 4.0 is how quickly they* made official ARB extensions for OpenGL that match DirectX 11’s capabilities. (NVidia hasn’t even managed to ship a DirectX 11 card yet, ATI’s HD5000 series has only been out for a few months, and OpenGL already has a spec.) OpenGL 4.0 exposes pretty much everything that is interesting in DirectX 11. By having official ARB extensions, developers like Laminar Research now know how we will take advantage of these new cards as we plan new features.

Things I Like

So are any of the new OpenGL 3.3 and 4.0 capabilities interesting? Well, there are three I like:

-

Dual-source blending. It is way beyond this blog to explain what this is or why anyone would care, and it won’t show up as a new OBJ ATTRibute or anything. But this extension does make it possible to optimize some bottlenecks in the internal rendering engine.

-

Instancing. Instancing is the ability to draw a mesh more than one time (with slight variants in each copy) with only one instruction to the graphics card. Since many games (like X-Plane) are limited in their ability to use the CPU to talk to the graphics card (we are “CPU bound” when rendering) the ability to ask for more work with fewer requests is a huge win.

There are a number of different ways to program “instancing” with OpenGL, but this particular extension is the one we prefer. It is not available on NVidia cards right now. So it’s nice to see it make it into the core spec – this is a signal that this particular draw path is considered important and will get attention.

-

The biggest feature in OpenGL 4.0 (and DirectX 11) is tessellation. Tessellation is the ability for the graphics card to turn a crude mesh with a few triangles into a detailed mesh with lots of triangles. You can see ATI demoing this capability here.

There are a lot of other extensions that make up OpenGL 3.3 and 4.0 but those are the big three for us.

* who is “they ” for OpenGL? Well, it’s the architectural review board (ARB) and the Khronos group, but in practice these groups are made up of employees from NVidia, ATI, Apple, Intel, and other companies, so it’s really a collective of people involved in OpenGL use. There’s a lot of input from hardware vendors, but if you read the OpenGL extensions, you’ll sometimes see game development studios get involved; Transgaming and Blizzard show up every now and then.

I’ve been working on a conformance test for X-Plane. The idea is simple, and not at all mine: X-Plane 945 can output a series of test images that are the same on each run. The images cover a variety of rendering conditions. If a video driver is broken, the images will be corrupted.

You can learn more about how this works here: I am working on the 945 timedemo tarball now.

The main driver for this is to help NVidia, ATI, and Apple to integrate X-Plane into their dedicated testing. With X-Plane as part of their test systems, they can catch driver bugs the easy way – the day after the code is changed, rather than months later after a series of angry web posts. X-plane 945 includes a number of new features as part of its framerate test to help with this process.

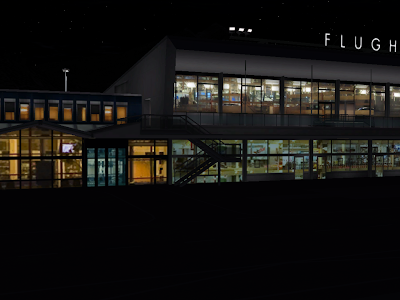

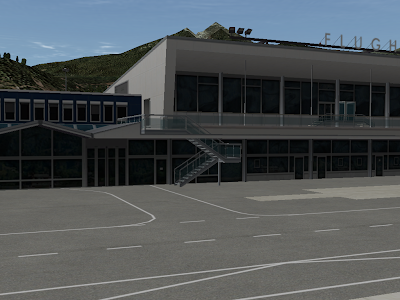

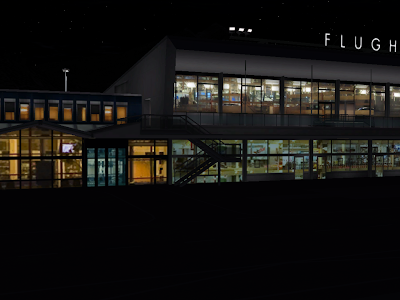

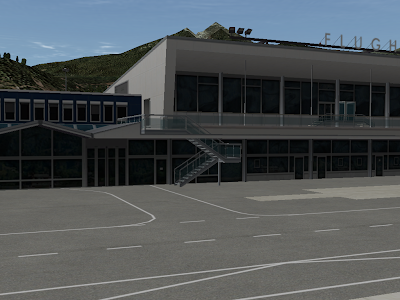

My hope is that this will benefit users (who will see less bugs) and the driver writers (who can get feedback on code changes in a uniform and reproducible manner). Here are the eight images in the sample conformance test I wrote, based on the LOWI custom airport scenery.

I’ve been on the road a lot for work, so my apologies to everyone whose email I am sitting on. Most of my time these days is being spent on new next-gen tech. But there are a few things I’m hoping to get done in the short term:

-

Cut a new time-demo test. This might seem like a low priority item, but it’s not. Apple, ATI and NVidia all run continuous automatic tests of their video drivers, with many applications and games. They have rooms full of computers that continuously run through 3 minute sections of Quake and Call of Duty, etc. If they introduce a driver bug while doing new development, these machines catch the problem immediately.

The new time demo (based on 945) will have a number of features to make X-Plane a more useful test case. If we can make X-Plane into a test case, then they can catch bugs early, and that means you don’t have to see them.

-

Bring WED 1.1 to beta. The only thing holding it back is the DSF exporter, and I did have about two hours to poke at it last week. I’m hoping if I can find just a few more hours, I can finish off the exporter.

-

Examine 950 bugs. I have half a dozen bug reports against 950 beta 1. 950 will be a small beta but also a slow one, because Austin and I have a lot of other things on our plates. If you haven’t heard back from me on a bug report, probably it’s still on my to-do list.

We’ll see how much of that I can get to in the next week.

The file loading code in 950 beta 1 for Windows is slower than 945. Sometimes. This will be “fixed” in beta 2. Here’s what happened:

The scenery system uses a number of small files. .ter files, multiple images, .objs, etc. This didn’t seem like a problem at first, and having everything in separate text files makes it easier to take apart a scenery pack and see what’s going on.

The problem is that as computers get bigger and faster, rather than a scenery pack growing bigger files, they are growing more files. The maximum texture size has doubled from 1024×1024 to 2048×2048. But with paged orthophotos, multicore, and a lot of VRAM, you could easily build a scenery pack with 10,000 images per DSF.

That’s exactly what people are doing, and the problem is that loading all of those tiny files is slow. Your hard drive is the ultimate example of “cheaper by the dozen” – it can load a single huge file at a high sustained data rate. But the combination of opening and closing files and jumping between them is horribly inefficient. 10,000 tiny .ter files is a hard drive’s worse nightmare.

In 950 beta 1 I tried to rewrite part of the low level file code to be quicker on Windows. It appeared to run 20% faster on my test of the LOWI demo area, so I left it in beta 1, only to find out later that it was about 100% slower on huge orthophoto scenery packs. I will be removing these “optimizations” in beta 2 to get back to the same speed we had before. (None of this affects Mac/Linux – the change was only for Windows.)

The long term solution (which we may have some day) is to have some kind of “packing” format to bundle up a number of small files so that X-Plane can read them more efficiently. An uncompressed zip file (that is, a zip where the actual contents aren’t compressed, just strung together) is one possible candidate – it would be easy for authors to work with and get the job done.

In the short term, for 950 beta 2, I am experimenting with code that loads only a fraction of the paged orthophoto textures ahead of time – this means that some (hopefully far away part) of the scenery will be “gray” until loaded, but the load time could be cut in half.

There is one thing you can do if you are making an orthophoto scenery pack: use the biggest textures you can. Not only is it good from a rendering perspective (fewer, larger textures means less CPU work telling the video card “it’s time to change textures”) but it’s good for loading too – fewer larger textures means fewer, larger total files, which is good for your hard disk.

(Thanks to Cam and Eric for doing heavy performance testing on some of the 950 beta builds!)

This blog post is for amateur plugin developers. By amateur I mean: some plugin developers are professional programmers by day, and are already familiar with all aspects of the software development progress. For those developers, the SDK is unsurprising and performance is simply a matter of applying standard practice: locate the worst performance problem, fix it, wash-rinse-repeat.

But we also have a dedicated set of amateur plugin developers – whether they had programming experience before as hobbyists, or learned C to take their add-ons to the next level, this group is very dedicated, but doesn’t have the years of professional experience to draw on.

If you’re in that second group, this post is for you. Explaining how to performance tune code is well beyond the scope of a blog post, but I do want to address some fundamental ideas.

I receive a number of questions about plugin performance (to which the answer is always “that’s not going to cause a performance problem”). It is understandable that programmers would be concerned about performance; X-Plane is a high performance environment, and a plugin that wrecks that will be rejected by users. But how do you go from worrying about performance to fixing it?

Measure, Measure, Measure, Measure.

If I had to go crazy and recite a sweaty and embarrassing mantra about performance tuning so that I could be humiliated on YouTube it would go: measure, measure, measure, measure.

If you want your plugin to be fast, the single most important thing to know is: you have to find performance problems by measurement, not by speculation, guessing or logic.

If you are unfamiliar with a problem domain (which means you are writing new code or a new algorithm – that is, doing something interesting), there is no way you are going to make a good guess as to where a performance problem is.

If you have a ton of experience in a domain, you still shouldn’t be guessing! After 5 years of working on X-Plane, I can make some good guesses as to where performance problems should be. But I only use those guesses to search in the likely places first! Even with good guesses, I rely on measurement and observation to make sure my guess wasn’t stupid. And even after 5 years of working on the rendering engine, my guesses are wrong more often than they are right. That’s just how performance tuning is: it’s really hard for us to guess where a performance problem might be.*

Fortunately, the most important thing to do, measuring real performance problems, is also the easiest, and requires no special tools. The number one way to check performance: remove the code in question! Simply remove your plugin and compare frame-rate. If removing the plugin does not improve fps, your plugin is not hurting fps.

It is very, very important to make frame-rate comparison measurements under equal conditions. If you measure with your plugin in the ocean and without your plugin at LOWI, the results are meaningless. Here’s a trick I use in X-Plane all the time: I set my new code to run only if the mouse is on the right half of the screen. That way I can be sitting at a fixed location, with the camera not moving, and by mousing around, I can very rapidly compare “with code”, “without code”. The camera doesn’t move, the flight model is doing the same thing – I have isolated just the routine in question. You can do the same thing in your plugin.

Understand Setup Vs. Execution

This is just a rule of thumb, and you cannot use this rule instead of measuring. But generally: libraries are organized so that “execution” code (doing stuff) is fast, while setup and cleanup code may not be. The SDK is definitely in this category. To give a few examples:

- Drawing with a texture in OpenGL is very fast. Loading up a texture is not fast.

- Reading a dataref is fast. Finding a dataref is not as fast.

- Opening a file is usually slower than reading a file.

- You can run a flight loop per frame without performance problems. But you should only register it once.

If you want to pick a general design pattern, separate setup from execution, and performance-tune them separately. You want things that happen all the time to be very fast, and you can be quite intolerant of performance problems in execution code. But if you have setup code in your execution code (e.g. you load your textures from disk during a draw callback) you are fighting the grain; the library you are using probably hasn’t tuned those setup calls to be as fast as the execution code.

Math And Logic Is Fast

Modern computers are astoundingly fast. If you are worried that doing a slightly more complex calculation will hurt frame-rate, don’t be. One of the most common questions about performance I get is: will my systems code slow down X-Plane. It probably won’t – the things you calculate in systems logic are trivial in computer-terms. (But – always measure, don’t just read my blog post!)

In order to have slow code you basically need one of two things:

- A loop. Once you start doing some math multiple times, it can add up. Adding numbers is fast. Adding numbers 4,000,000,000 times is not fast. It only takes one for-loop to make fast code slow.

- A sub-routine. The subroutine could be doing anything, including a loop. Once you start calling other people’s code, your code might get slow.

This is where the professionals have a certain edge: they know how much a set of standard computer operations “cost” in terms of performance. What really happens when you allocate a block of memory? Open a file? If you understand everything going on to make those things happen, you can have a good idea of how expensive they are.

Fortunately, you don’t need to know. You need to measure!

SDK Callbacks Are Fast (Enough)

The SDK’s XPLM library serves as a mediator between plugins and X-Plane. Fortunately, the mediation infrastructure is reasonably fast. Mediation includes things like requesting a dataref from another plugin, or firing off a draw callback. This “callback” overhead contains no loops internally, and thus it is fast enough that you won’t have performance problems doing it correctly. One draw callback that runs every frame? Not a performance problem. Read a dataref? Not a performance problem. (Read a dataref 4,000,000 times inside a for-loop…well, that can be slow, as can anything!)

However you should be aware that some plugin routines “do work”. For example, XPLMDrawObject doesn’t just do mediation (into X-Plane), it actually draws the object. Calls that do “real work” do have the potential to be slower.

Be ware of one exception: a dataref read looks to you like a request for data. But really it happens in two parts. First the SDK makes a call into the other plugin that provides the data (often but not always X-Plane itself) and then that other plugin comes up with the data. So whenI say “dataref reads are fast” what I really mean is: the part of a dataref read that the SDK takes care of is fast. If the dataref read goes into a badly written plugin, the read could be very, very slow. All of the datarefs inside X-Plane vary from fast to very fast, but if you are reading data from another plugin, all bets are off.

Of course, all bets are off anyway. Did I mention you have to measure?

* Why can’t we guess? The answer is: abstraction. Basically well structured code uses libraries, functions, etc. to hide implementation and make the computer seem easier to work with. But because many challenging problems are hidden from view (which is a good thing) it’s hard to know how much real work is being done inside the black box. Build a black box out of black boxes, then do it again a few time, and the information about how fast a function is has bee

n obscured several times over!

There’s a slight performance win to be had by grouping taxiways by their surface type.

Now clearly if you have to have an “interlocked” pattern of asphalt on top of concrete, on top of asphalt, this isn’t an option.

But where you do have the flexibility to reorder, if you can group your work by surface type, X-Plane can sometimes cut down on the number of texture changes, which is good for framerate.

X-Plane will try to do this optimization for you, but X-Plane’s determination of “independent” taxiways (taxiways whose draw order can be swapped without a visual artifact) is a bit limited and can only catch simple cases.

For what it’s worth, interlocked patterns of surfaces were much more a problem with old X-Plane 6/7 type airport layouts, where the taxiways were sorted by size, and there could be hundreds of small pieces of pavement.

I have blogged in the past regarding the rendering settings in X-Plane, but this seems to come up periodically, so here we go again. Invariably someone asks the question: “what computer do I have to buy to run X-Plane with all of the sliders set to maximum?”

I now have an answer, in the form of a question: “How hungry do you have to be to clean your plate at an all-you-can-eat buffet?”

There is no amount of hungry that will ever be enough to eat all of the food at an all you can eat buffet – you can always ask for more. And when it comes to rendering settings and global scenery, X-Plane is (whenever possible) the same way. You can always set more traffic, more birds, more objects, more FSAA.

Now the all-you-can-eat buffet doesn’t have infinite amounts of food in the building – just enough that they know that they won’t run out. And X-Plane is the same way. There is a maximum if you set everything all the way up, but we try to make sure that no one is going to hit a point where they want more eye candy but they’ve maxed out the settings. Eat all you want, we’ve got more.

Why on earth would we set up X-Plane like this? The answer is choice.

If you go to an all you can eat buffet, you can fill up on nothing but potatos, or you can have five pieces of chicken. It’s up to you. X-Plane is the same way – you decide if you want objects to be visible farther away or more densely. Would you rather have roads or trees? Birds or high frame-rate? You decide!

Not everyone’s appetite is the same, and not everyone’s taste is the same. This is very true when it comes to flight simulation. There are huge variations in hardware capability, target framerate (some users don’t mind 20 fps, some demand 80 fps) and in what part of the visual experience people care about most (objects vs. FSAA vs. visibility distance, etc).

Given such a heterogeneous environment, the only way to meet the needs of a wide group of users is to present choice, and make sure that we have enough of everything.

So when you go to set the rendering settings, don’t think that setting objects to anything less than maximum is like only eating half the steak you bought at a steak-house. Rather, the rendering settings are like picking which food from the buffet makes it to your plate. You choose how much you want based on what you can consume, and you pick and choose what is most desirable to you. And like an all you can eat buffet, don’t eat too much – the results won’t be pleasant!

I have blogged about this before, but I keep seeing this issue come up in the forums, so I want to go over it again. If you want to effectively tune X-Plane to trade off maximum visual quality with desired framerate, you must first reduce your rendering settings all the way to the bottom, then work your way up. Let me explain with an analogy.

I have fallen off my motorcycle and hit my head, skinned my knee, and broken my arm; the bone is sticking right out of my skin! Ouch! So I go to the hospital and the Doctor examines me. Here is how the conversation goes:

Dr: How does your arm feel?

Me: My arm hurts so much! OUCH!

Dr: And how does your leg feel?

Me: My arm is burning and stinging! Please make it stop!

Dr: Do you feel dizzy or light headed?

Me: Please fix my arm!!!!!!!!

Clearly with a bone sticking through my skin, there is no point in doing a physical examination. My arm hurts so much that I can’t tell the Doctor whether I have any other aches or pain. I feel one thing: the arm.

What does this have to do with framerate? Well, framerate is just like pain. The low framerate you see is caused by only the one worst problem with your setup. If your graphics card is a little bit overloaded, you are a hair short on VRAM, and your CPU is absolutely being killed, then the low framerate you see is totally because of the CPU. The weakest link decides your framerate. And like the Doctor, if we go trying to deal with the VRAM problem, we will see no change because it’s the CPU that hurts the most.

This is what I see over and over: a user is running X-Plane, his framerate is bad, and he has turned some but not all of the settings down. At this point the user is usually pretty grumpy – his visuals now look bad and his framerate is poor.

The problem is that the user hasn’t turned down the setting that really matters. This is why the first thing you need to do in order to tune framerate is to turn everything down, so that you are running with framerate at least as high as what you want for your target value. Then you can turn settings up one at a time and watch which one lowers framerate.

(Don’t worry, you’re not going to stay at the lowest settings. The key is just to always be turning settings up, not down.)

Here are some of the settings I see that need to be turned down but often are not.

- Full screen anti-aliasing. (FSAA) Always turn FSAA down to none. FSAA will kill fps on any graphics card that is fill rate limited.

- Pixel shader effects – every one of these should be turned off to start. And when you do start them, try them one at a time and have the water reflections off – work your way up in small steps. The gap from shaders without volumetric fog, shadows, reflections and per pixel lighting to shaders with all of these effects is huge!

- Turn objects all the way down to default, or even off. If your CPU is the problem, objects could be a factor.

- Leave texture compression on in your “rock bottom” settings. Texture compression improves fps and lowers visual quality, so having the check box be on is the minimal setting.

- Don’t run at a huge screen res or FOV. Run 1024×768 and 50 degrees FOV.

What happens if you turn everything down and you still see 19 fps? Now it’s time to investigate your video drivers and control panel settings. If your setup is even remotely better than minimum hardware, it should scream when all of those settings are turned down. If you still see low fps, check drivers, check control panel settings. There are a lot of control panel settings, for example, that will completely kill framerate.

In MeshTool 2.0, you can specify how wet orthophotos are handled. There are three possibilities:

- The orthophoto has no alpha-based water. The alpha channel will be ignored.

- The orthophoto has alpha-based water. Draw water under the alpha, but for physics, make the triangles act “solid”.

- The orthophoto has alpha-based water. Draw water under teh alpha, and for physics make the triangles act “wet”.

The reason for 2 and 3 is that the X-Plane physics engine doesn’t look at your alpha channel – wet/dry polygons are decided on a per triangle basis. (The typical work-around is to use the “mask” feature in MeshTool to make some parts of the orthophoto be physics-wet and some physics-solid. This is described in the MeshTool README.)

Whenever possible: don’t use alpha-based water at all. It is certainly easy to set all of your orthophotos to alpha-water + physics-solid, but there are three costs to this:

- You eat a lot of fill rate. X-Plane manages alpha=water by drawing the water underneath the entire orthophoto, then painting over it with the orthophoto. This is fill-rate expensive. If you know there is no alpha, tell MeshTool, so it can avoid creating that “under-layer” of water.

- If the terrain is very mountainous, you may get Z-buffer artifacts from the layering, particularly for thin, spikey mountains (which probably aren’t wet anyway).

- The reflection engine tries to figure out the “surface level” of the water, but it doesn’t understand the alpha channel on top of the water. So all of that water “under” your mountain or hill is going to throw the reflection engine into hysterics.

Limiting the use of water under your orthophotos fixes all three problems.